If you listened to my 1-hour talk on how I got into Stoicism, you would know that out of all the mental health ailments, anxiety has been the one that has caused most problems for me.

I am no stranger to panic attacks, hypervigilance, and hypochondria. For years, no matter what I did or where I went, my anxious mind seemed to follow me.

In the grip of anxiety, I could not take in what was going on around me. My mind had tunnel vision, focusing only on the danger that might occur while urging me to flee and avoid catastrophe at all costs.

Fortunately, I have overcome anxious episodes and Stoic philosophy has played a major role in providing a framework for my progress.

In this post, I will be sharing Stoic quotes on the problems and remedies for anxiety. The main problem I had with anxiety is that it is very difficult to reason with yourself when you are extremely anxious. Seneca described it beautifully:

No fear is so ruinous and so uncontrollable as panic fear. For other fears are groundless, but this fear is witless.

In my Stoic Guide to Overcoming Anxiety podcast, I explained that it is worth distinguishing between fear and anxiety because while similar, they run on different systems. But in this post, I will use the terms fear and anxiety to describe any kind of anxious/fearful emotion that causes persistent problems in your life.

5 Problems with Anxiety

Stoic Quotes on Anxiety that Locate the Core Issues with This Emotion

Problem #1: Anxiety Makes Us Suffer Many Times Over

Typically, if the thing we fear happening happens to us, it will cause us suffering. But the very feeling of anxiety about this suffering in itself is a form of suffering.

If foolishness fears some evil, it is burdened by the anticipation of it, just as if the evil had already come. What it fears lest it suffer, it suffers already through fear…. What then is more insane than to be tortured by things yet to be – not to save your strength for actual suffering, but to summon and accelerate your wretchedness? You should put it off if you cannot be rid of it.

— Seneca, Epistles 74.32–34

The anxiety about the suffering is also very often worse and more drawn out than the event we fear.

“There are more things, Lucilius, that frighten us than affect us; we suffer more often in conjecture than in reality…. We magnify our sorrow, or we imagine it, or we get ahead of it.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.4–5

Problem #2: Anxiety Stops Us From Enjoying An Acceptable Present

Regardless of what you think about mindfulness and “living in the present,” one thing is incontestable: the times when we are lost in thought, thinking without knowing we are thinking are unlikely to most joyous and memorable parts of our life.

When those thoughts happen to be anxious thoughts, a very acceptable and even "good" present will be unbearable.

Things may in fact be just fine, but an anxious mind will destroy that perspective.

This is related to problem #1 but not the same. Anxiety doesn’t just cause us pain on multiple occasions, it takes away the joy in our life too.

It is ruinous when a mind is worried about the future, wretched before its wretchedness begins, anxious that it may forever hold on to the things that bring it pleasure. For such a mind will never be at rest, and in awaiting the future it loses sight of what it might have enjoyed in the present. The fear of losing a thing is as bad as regret at having lost it.

— Seneca, Epistles 98.6

Bygone things and things yet to be are both absent; we feel neither of them. And there is no pain except from what you feel.

— Seneca, Epistles 74.34

Problem #3: Anxiety Makes Us Act Foolishly

When we are very anxious, we get told by our body to just fight, flee, or freeze as a survival mechanism. But these responses are often not the wisest way to respond.

For example, how many pointless fights have been started due to anxiety? How many road accidents? How many bad life choices?

Well, then, we act like deer. When they are frightened and flee the feathers that the hunters are waving at them, where do they turn, toward what place of safety do they retreat? Into the nets. They are destroyed by confusing what should be regarded with fear with what might be regarded with confidence.

— Epictetus, Discourses 2.1.8

Problem #4: Anxiety Builds in Momentum

Finally, fear and other emotions tend to accumulate once they get going. That is why Seneca is a skeptic about the possibility of indulging emotions moderately.

If reason prevails, the emotions will not even get started; while if they begin in defiance of reason, they will continue in defiance of reason. It is easier to stop their beginnings than to control them once they gather force. This “moderation” is therefore deceptive and useless: we should regard it in the same light as if someone should recommend being “moderately insane” or “moderately sick.”

— Seneca, Epistles 85.9

Problem #5: Anxiety Makes You a Slave

The goal of philosophy is to develop wisdom and ultimately gain a sense of freedom regardless of our circumstances. If we are constantly plagued with anxiety, we will find it hard to be free at all, and in fact, will live life in a state of enslavement to our fears.

For this reason, the Stoics see anxiety as a form of sickness (which is similar to our medical assessment) and see it as a very important goal for the philosopher to cure it.

Even when there is nothing wrong, nor anything sure to go wrong in the future, most mortals exist in a fever of anxiety.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.13

No one who is afraid or distressed or troubled is free; and whoever is released from distress and fear and trouble, is in the same way released from slavery.

— Epictetus, Discourses 2.1.24

Stoic Antidotes to Anxiety

4 Stoic Remedies for Anxiety and Panic

Anxiety Antidote #1: Rational Scrutiny

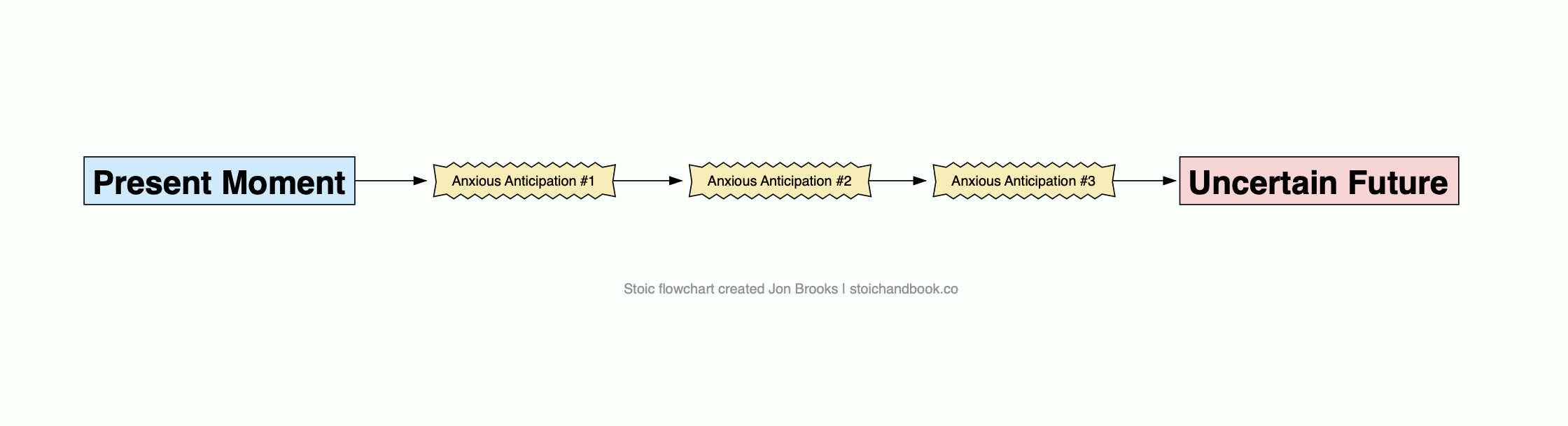

If you break anxiety down, you will find that it follows this mental sequence:

- The anxious person has a belief about something that will happen in the future

- The anxious person believes this thing will be terrible and dangerous

- The anxious person accepts that this thing is worth getting upset about in the present so as to avoid it

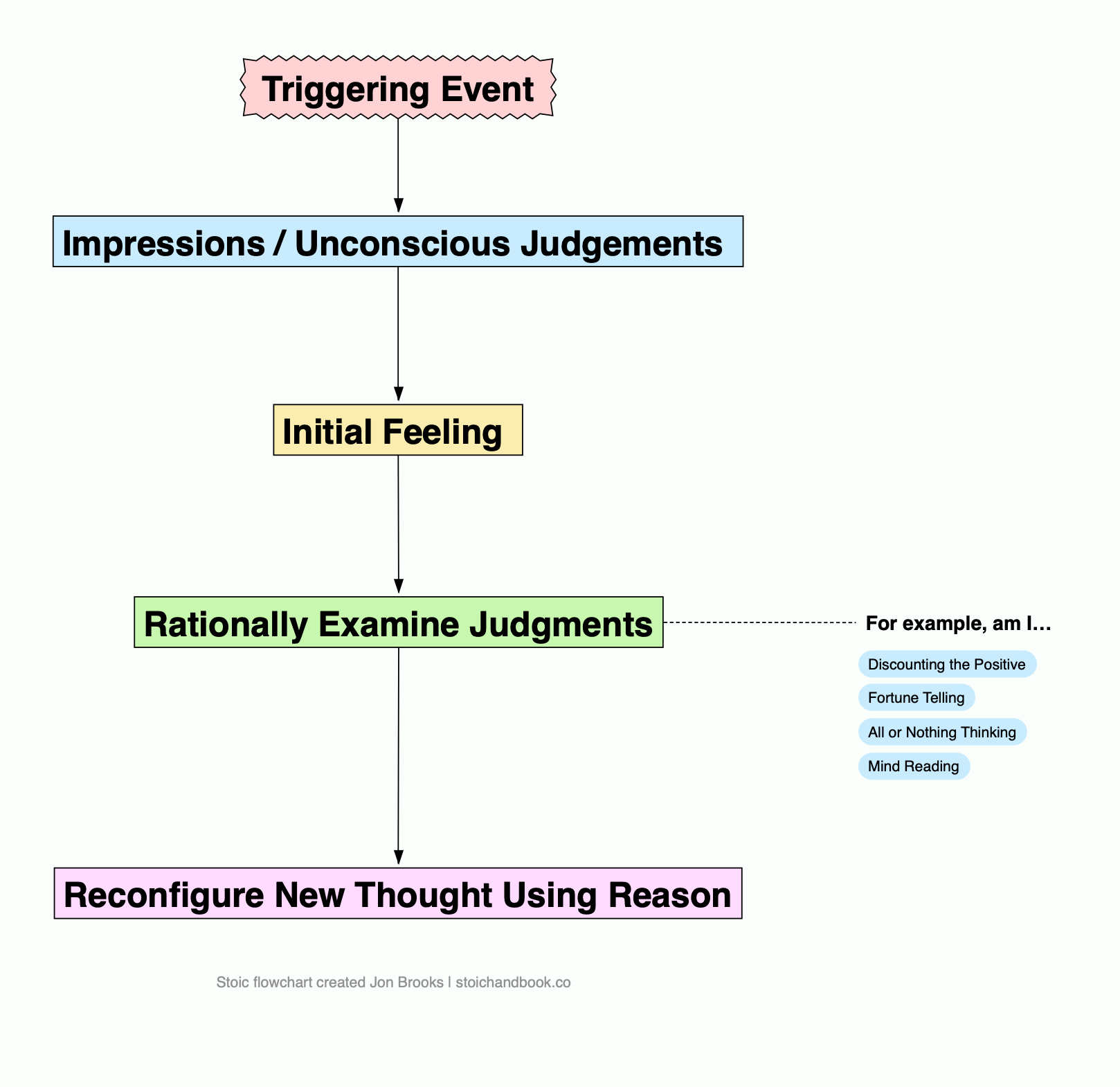

Similar to styles of therapy like CBT, which was inspired by Stoic thought, a Stoic would be skeptical of these beliefs and attempt to dismantle them in the light of reason.

We should examine our beliefs against actual evidence and try to spot the distortions in our thinking.

We do not disprove and overthrow by argument the things that cause our fear; we do not examine into them; we tremble and retreat just like soldiers who have abandoned their camp because of a dust-cloud raised by stampeding cattle, or who are thrown into a panic by the spreading of some rumor of unknown veracity. And somehow or other it is the false report that disturbs us most. For truth has its own definite boundaries, but that which arises from uncertainty is delivered over to guesswork and the license of a mind in terror.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.8

Anxiety Antidote #2: Rational Optimism

Whenever we have anxiety, we can surely tell that our mind is biased in a certain direction. At first, we may use rational scrutinty to try and remove that bias altogether, but if this fails we can instead nudge the bias in a different direction.

In other words, if we are going to be biased, we should be biased in a way that leads to less suffering and more tranquility. You can think of this approach as psychologically rigging the game of life in your favor.

Weigh your hopes against your fears. When everything is uncertain, favor your own side: believe what you prefer. If fear obtains more votes, bend more the other way nevertheless and stop troubling yourself.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.13

Anxiety Antidote #3: Embrace Real Suffering, Reject Imagined Suffering

If you happen to be in a situation that is inflicting suffering upon you, by all means, do your best to deal with it and grow in strength as a practicing Stoic. But if the suffering is somewhere out there in the mystical future why suffer now when you might not need to suffer at all?

The things that terrify you, as if they were about to happen, may never come; certainly they have not come yet. Some things torment us more than they should, some before they should, some when they should not torment us at all.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.4–5

It is likely that some bad thing will happen in the future, but it is not happening now. How often has the unexpected happened! How often has the expected never come to pass! … Many things may intervene that will cause an impending or present danger to stop, or come to an end, or pass over to threaten someone else. A fire has opened up a means of escape; a disaster has let some men down gently; the sword has sometimes been withdrawn from the very throat; men have survived their executioners. Even ill fate has its quirks. Perhaps it will be, perhaps it will not be; meanwhile it is not.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.10, 11

The next time you are imagining all of the "bad" things that might happen in the future, instead ask:

"Right this moment, is more or less everything okay?"

The answer, more often than not, will be "yes."

Anxiety Antidote #4: Remember How Well You Can Cope

A large part of our anxiety stems from the erroneous belief that when this “terrible” thing happens, we won’t be able to handle it. But the evidence in our lives suggests that we are pretty good at coping.

After all, we’ve made it this far.

I will conduct you to peace of mind by another route: if you would put off all worry, assume that what you fear may happen will certainly happen. Whatever the evil may be, measure it in your own mind, and estimate the amount of your fear. You will soon understand that what you fear is either not great or not of long duration.

— Seneca, Epistles 24.2

Let someone else say, “Perhaps the worst will not happen.” You say, “And what if it does? Let us see who wins. Perhaps it is happening for my benefit, and such a death will dignify my life.” The hemlock made Socrates great. Pry from his hand Cato’s sword – the vindicator of his freedom – and you take away the greater part of his glory.

— Seneca, Epistles 13.14

Do not let things still in the future disturb you. For you will come to them, if need be, carrying the same reason you now employ when dealing with things in the present.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 7.8