How Stoics Sympathise with Others

Chapter 16 / 53 Enchiridion

Stoics often get this unfair reputation for being cold and lacking in compassion.

This is less to do with Stoic philosophy, however, and more to do with the misinterpretation of Stoic principles.

If you read Seneca’s letters, you see a chirpy character who is excited to help his friend Lucilius overcome his issues. In his letters of consolation, Seneca writes page after page out of a deep yearning to help those who are suffering needlessly.

These are not the letters of a robot, but rather the letters of someone who has suffered, liberated himself from a large portion of that suffering, and now wants others to achieve similar freedom.

This is Stoicism in action.

In today’s lesson, Epictetus gives us a guide to use when we meet people who are going through a very difficult time.

The idea, as is often the case with Stoicism, is to find a balance.

In this case, the balance is between completely losing yourself in the misery of another person and on the other side being cold and callous.

The principle can be summarised as follows:

Love your neighbour and wish them well during hard times. But at the same time, do not let their current perceptions of reality distort your own judgments.

I/ Remember Your Stoic Principles

We will all experience loss in many forms throughout our lifetimes.

In our own life, we practice Stoicism to better cope with such loss, but we should not forget our principles when others also experience loss.

If you see someone in great pain due to the death of a loved one or the end of a job, don’t fall into the trap of thinking their situation is truly “bad.”

Remember the principle that “it is not events that disturb us, but our view of them.”

This applies to both ourselves and others.

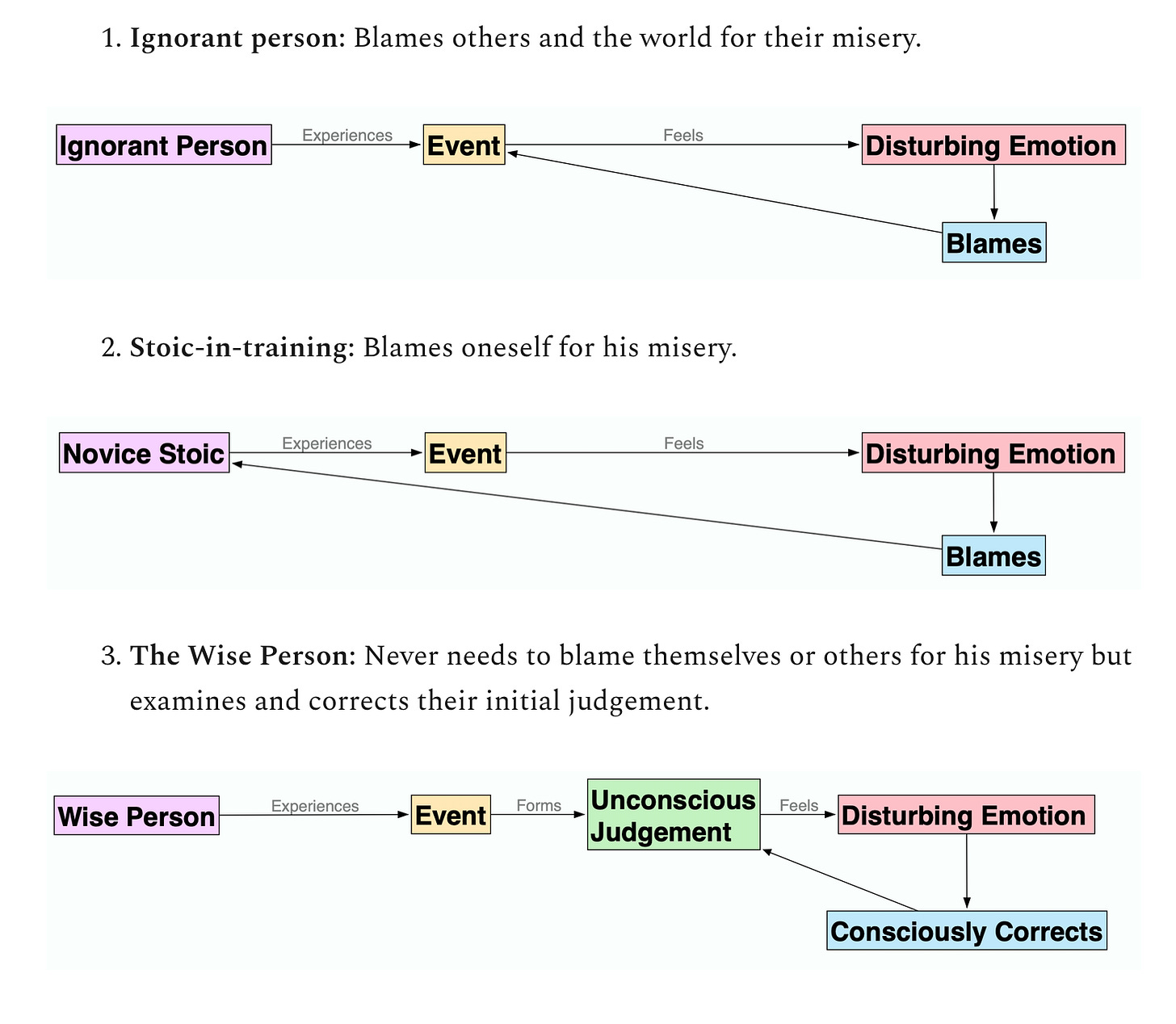

In Chapter 5, of the Stoic Handbook, we looked at the 3 levels of wise interpretation:

To remember that there is no true “good” or “bad” in any event, we can reflect on the following fact:

Human beings can respond to the same event in different ways depending on the way they frame that event. If reality was hardcoded, everyone would experience identical feelings when the same event happens.

II/ Sympathise Outwardly

However, just because you see that no event can be truly good or bad, this doesn’t mean you should act cold and robot-like with those who are in pain.

Comfort your friends, help them through their suffering, and go so far as to share outwardly in their grief.

But do not allow yourself to get sucked blindly into their emotional vortex. This is not good for you, nor them.

ENCHIRIDION CHAPTER SIXTEEN, EPICTETUS, TRANSLATION BY ROBERT DOBBIN:

Whenever you see someone in tears, distraught because they are parted from a child, or have met with some material loss, be careful lest the impression move you to believe that their circumstances are truly bad. Have ready the reflection that they are not upset by what happened – because other people are not upset when the same thing happens to them – but by their own view of the matter. Nevertheless, you should not disdain to sympathise with them, at least with comforting words, or even to the extent of sharing outwardly in their grief. But do not commiserate with your whole heart and soul.